Gull Poop

Author: Norm Budnitz

Seems like a catchy title, doesn’t it. Well, I wanted to catch your eye, because there’s a movement going on, and it may be significant.

Each winter since 1977, the New Hope Audubon Society has sponsored the Jordan Lake Christmas Bird Count. A hardy group of volunteers, call them citizen scientists if you’d like, spread out across a 15-mile diameter circle centered on Jordan Lake in Chatham County, North Carolina, usually on the first Sunday of the new year. We go out in small parties (usually 1-4 people) and count every single bird we can identify by sight or sound. This record is a snapshot of the bird population present on that day.

Figure. 1. An adult Ring-billed Gull

– Photograph by Dennis Forsythe

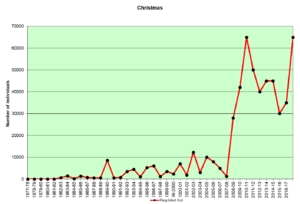

On January 4, 2009, the party covering the central part of Jordan Lake (led by Tom Krakauer) found themselves counting an enormous flock of Ring-billed Gulls (Larus delawarensis). They had reported several thousand gulls each year during the preceding decade, but this year they estimated 28,000 gulls. The next year, they reported 42,000 gulls. And in 2011, the number jumped to a staggering 65,000. Since then, the numbers have dropped off a bit, down to a ‘mere’ 35,000 to 50,000 each year. That is a lot of gulls and, as we shall see, a lot of gull poop!

Figure 2. This graph shows the Ring-billed Gull numbers since the inception of the count in 1977. The South Wake Landfill opened in 2008, and that’s when the gull numbers on the lake began to rise.

Ring-billed Gulls breed in the summer in the northern tier of states in the US and across the Canadian provinces. They move south in the fall and spend the winter along the east and west coasts of the US, across the southern tier of states, and south into Mexico. In the winter, they congregate near water—coastal beaches, inland lakes, and along river systems. In central North Carolina, ‘our’ gulls roost on Falls and Jordan Lakes, starting in mid to late fall. The Jordan Lake gulls roost on the central part of the lake, between Ebenezer Point on the east and Vista Point on the west. In the morning, about an hour after sunrise, most of the gulls leave the lake and fly east about 10 miles to the South Wake Landfill in Apex, North Carolina. In late afternoon, after a day of feasting on the refuse generated by close to a million Wake County residents, the gulls return to the lake to roost for the night.

Figure 3. Approximately 10,000 gulls at South Wake County Landfill — Photograph by Scott Winton

Figure 4. Gulls on the beach at Ebenezer Point, Jordan Lake — Photograph by Jim George

The first question you might ask is, “How does one count that many birds?” We have used two methods. The first entails standing in a strategic spot, starting around 8:00 AM, where the vast majority of gulls fly overhead toward the east in a steady stream for about an hour. The Ebenezer Church Boat Ramp or the bridge across Beaver Creek fill the bill. With a little practice, an observer can estimate clusters of 50 or 100 gulls. Then it’s a question of counting the number of clusters.

Figure 5. Approximately 50 gulls – Photograph by Norm Budnitz

The second technique can be used late in the afternoon after most of the gulls have returned to roost, but while there is still enough light to see. In this case, the gulls drop down to sit on the water surface. With a spotting scope, the observer can count the number of gulls in one scope field. Then it’s just a matter of counting the number of ‘scope fields’ of gulls. This method is probably not as accurate as the first method because some gulls may be ‘hidden’ behind others or by any wave action on the lake. However, when two independent parties have used each method in a given year, we have recorded comparable results, so we feel confident that our estimates are reasonable.

I mentioned these results to Scott Winton, then a PhD student at the Wetland Center, Nicholas School of the Environment, Duke University. As a specialist in water quality issues, Scott was immediately intrigued by the question of the transfer of nutrients by the gulls from the landfill to the lake. He and his colleague, Mark River, gathered more data and, using models generated by other researchers, have published their results in the paper cited at the end of this article.

One thing they had to do was visit the landfill and collect fecal samples, i.e., scoop the poop. When gulls eat and digest the organic material they scavenge at the landfill, they absorb the good parts and excrete the leftovers. Their poop, then, includes nutrients of interest to scientists—in particular, nitrogen and phosphorus compounds that are known pollutants in lakes. Although some of that poop is simply left at the landfill, some of it is saved and deposited later (to put it delicately) at the roost site on the lake. They also looked at winter gull population estimates on eBird for many other inland lakes across the US and Canada. Their goal was to estimate the impact these birds might be having by recycling nutrients from landfills to these lakes and, perhaps, contributing to their pollution levels.

What did Scott and Mark find? They estimate that the gulls transport about 7 tons of nitrogen (N) and about 1 ton of phosphorus (P) each winter. The pollution reduction targets (set by the Environmental Protection Agency of the federal government) for these chemicals in Jordan Lake are 175 tons of N and about 2 tons of P. So, if officials could eliminate this nutrient transport by the gulls by somehow excluding their access to the landfill, they could reduce the pollution loads by about 4% of N and about 50% of P. This could save the state about 2.7 million dollars each year in lake pollution clean-up costs.

As Winton and River point out, this reduction would not solve Jordan Lake’s pollution problems. There are many other sources of nutrient input into the lake—farmland, residential areas with impervious surfaces (roads), input from municipalities upstream, etc. But controlling the gull population would save money that could be spent on cleaning up wetlands and streams in other areas or could save the cost of taking agricultural land out of production. Farmers put fertilizer on their fields. Some of this fertilizer washes into rivers and streams and eventually finds its way into lakes like Jordan Lake (and eventually into the Atlantic Ocean). To put this another way, the amount of phosphorus transferred by the gulls each year is the equivalent of the amount that comes from approximately 2,000 acres of corn or 11,000 acres of pasture.

Keeping the gulls out of the landfill might be expensive, but there are non-lethal ways to do it. Again, as Winton and River note, Ring-billed Gulls are not an endangered species and their huge population numbers are the result of human waste storage and disposal activities. If we could clean up our act, there would be fewer gulls and less gull poop in our waters. I haven’t even mentioned Falls Lake and all the other inland lakes with large gull populations across the continent, though Winton and River do in their paper. Stop gulls from feeding in landfills. Stop gulls from then pooping in our lakes. Save millions of dollars. Everybody wins. Except the gulls, I guess.

Reference: Winton, R.S., River, M., The Biogeochemical Implications of Massive Gull

Flocks at Landfills, Water Research (2017), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2017.05.076